Exploited for centuries and described as the poorest of the poor even in a poverty-stricken country like Angola, the last San people in this southern African country are very slowly getting back on their feet.

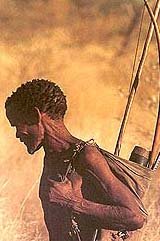

Exploited for centuries and described as the poorest of the poor even in a poverty-stricken country like Angola, the last San people in this southern African country are very slowly getting back on their feet.The San, also known as Bushmen, are widely considered as the descendents of Southern Africa's first inhabitants, but their lives, particularly during Angola's three decades of civil war, have been fraught with hunger, discrimination and exploitation.

Fieldwork conducted after the end of Angola's conflict in April 2002 enabled researchers to make contact with some of the country's San people, document their living conditions and culture, and propose measures to help them.

During the last two years, the Irish Catholic Agency for World Development, TROCAIRE; the Windhoek-based Working Group of Indigenous Minorities in Southern Africa (WIMSA); and the Angolan NGO, Organizacao Crista de Apoio ao Desenvolvimento Comunitario (OCADEC), have supported around 3,500 !Xun San living in southern Angola with food, seeds, agricultural tools and advice on obtaining identity documents.

According to Axel Thoma, a WIMSA coordinator for the last 10 years and an expert who has worked with the San in Southern Africa for 25 years, this support, designed to help people make a start towards self-sufficiency, was beginning to bear fruit.

He said the San's food security situation had improved dramatically, in part because of the help they had received but also due to their commitment and natural farming skills."

In 2004 the San achieved 80 percent food security because the rains were good and people worked hard in the fields, demonstrating how much they appreciated this input [assistance]," Thoma told IRIN.

A lack of rain in the 2005-06 season has seen the food security situation again dip to around 40 to 50 percent, but Thoma is not unduly concerned."

We are not intending to come in with food intervention to bridge the next dry year," he said. "We are working with a group of people who have managed to survive 27 years of war as outcasts, so we don't consider 40 to 50 percent food security a failure; we consider it on a par with the standards of the San who are used to seasons with less food."

Thoma also applauded the Angolan government's land policy, which recognises that all rural communities, including the San, need to have a secure land base and a safe home."

The government of Angola is very seriously working on land title deeds for communities. They have this idea that an entire community has the right to manage land for agriculture, housing, schools, natural resources or whatever. This has not happened a lot in Southern Africa - the Angolan government is a step ahead of neighbouring countries - they are looking at the situation without prejudice towards the San," Thoma said.

MUCH TO BE DONE

What was needed now, Thoma believed, was to broaden the San's agricultural knowledge to cover livestock and perennial crops. "We are pushing for programmes where people have their own animals to give [them] milk and meat."

But, as before, any assistance to the San will not be a gift, and they will have to 'pay back' the cows and goats when they reproduce. This goes some way to easing one of Thoma's biggest fears: that the community will become dependent on food aid and lose the resourcefulness that has helped it to survive for thousands of years.

The aid organisations want the San to look beyond their current agricultural output of maize, millet, beans, melons and pumpkin. "We are also looking into long-term crops - manioc, cassava - and looking at fruit trees, such as mango, papaya, guava and avocadoes. We want to encourage the San to plant something which lasts years, so that they have long-term resources to tap into," he explained.

Thoma would also like to motivate these natural hunter-gatherers to look again to their native bushland and collect the wild plants, berries, roots and tubers that provide nourishment and ingredients for traditional remedies, and keep alive their traditional knowledge.

"The gathering of food has stopped because the land is over-grazed, but from a development point of view, we want to encourage people to use traditional food and medicine from the bush. It is very good and very nutritious," he said."

Collecting food is a communal activity carried out by the young, the women, the elders. It is like a school for young toddlers, who will discover how to identify plants and whether they are edible or poisonous. By not gathering food, the learning process has been harmed because there is nothing else to challenge these children - there is not much to do, parents get depressed, and life becomes dull. It is important to encourage traditional skills and maintain them," Thoma noted.

With this support, he hopes Angola's San - who have faced a history of discrimination and persecution by other ethnic groups - will become self-sufficient within two generations.

"The San in Angola are very advanced compared to their [San] neighbours: they have a lot more knowledge about agriculture; they are good at cultivating their land; they have an advantage because they will very quickly reach the ability to look after themselves and not become dependent on development organisations," he pointed out.

"This frees the mind and they can look at their future development beyond filling their bellies; they can look at education. I can see this happening very much quicker in Angola than in other countries," Thoma predicted.

He estimated that 99 percent of Angola's San population were illiterate, and while San leaders were eager to see their children attend school, few could afford to do so. Of those who did, many gave up when faced with bullying and discrimination because of their typically unkempt appearance.

TROCAIRE, WIMSA and OCADEC want to expand their programmes to include the estimated 3,500 to 4,000 Khwe San believed to be surviving in landmine-strewn southeastern Angola, but the organisations worry that too much assistance could jeopardise their development strategy.

Thoma says they are "walking a fine line" between supporting the San and wiping out the natural skills and resourcefulness that these hunter-gatherers have cultivated over the centuries.

"What I fear now is that, as more people show an interest, the development strategy could be undermined by do-gooders who think 50 percent food security is not good enough," Thoma commented, adding that in the past they had been criticised by some donors for allowing the San to go hungry.

He argued that their broad development strategy was the right one for maintaining long-standing San traditions.

"We want to help a minority group of people stay alive within their cultural boundaries. This is a group of people who were in slavery for a long time, who have been pushed down for the last 300 years. We want to help them pick themselves up again and to find pride in their existence," he said."

Southern Africa, including Angola, has a real richness here. The San are 'Adam and Eve' - they are the first people, according to DNA proof. This is an exceptional place and exceptional people we should be proud of. We should make sure these people have the right to live close to their culture and not be forcefully modernised into a global world," he maintained.

DNA evidence suggests that the San could have lived in the region 100,000 years ago. An estimated 100,000 San survive - 50,000 in Botswana, 35,000 in Namibia, 5,000 in South Africa and the rest in Angola, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

Reproduced with the kind permission of IRIN

Copyright IRIN 2006

Disclaimer: This article does not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations or its agencies